A couple of days ago my medical director and I had a short discussion about teaching pulmonary fellows to read PFTs and agreed that in order to be good at interpreting PFTs it isn’t the basic algorithms that are hard, it’s gaining an understanding of test quality and testing problems. My medical director then suggested this topic. At first I wasn’t sure I could find 10 errors but after spending a couple hours digging through my teaching files I managed to come up with just a few more than that. So strictly speaking it’s not a top 10 list but I kept the title because I liked it.

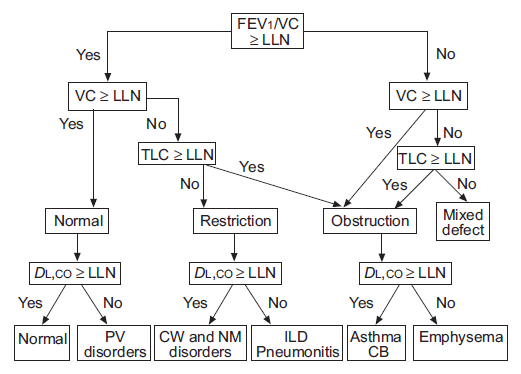

Spirometry errors and mistakes seem to fall into four categories: demographics, reference equations, testing and interpretation.

Demographics:

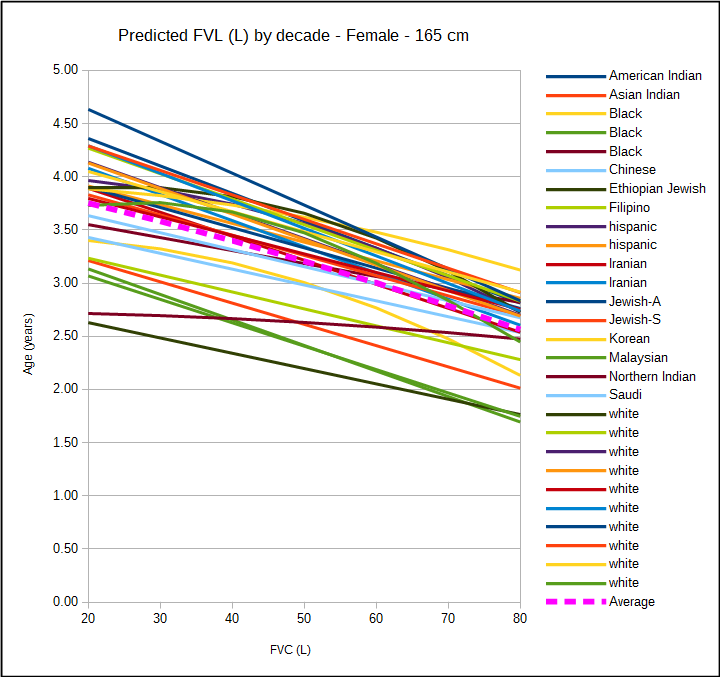

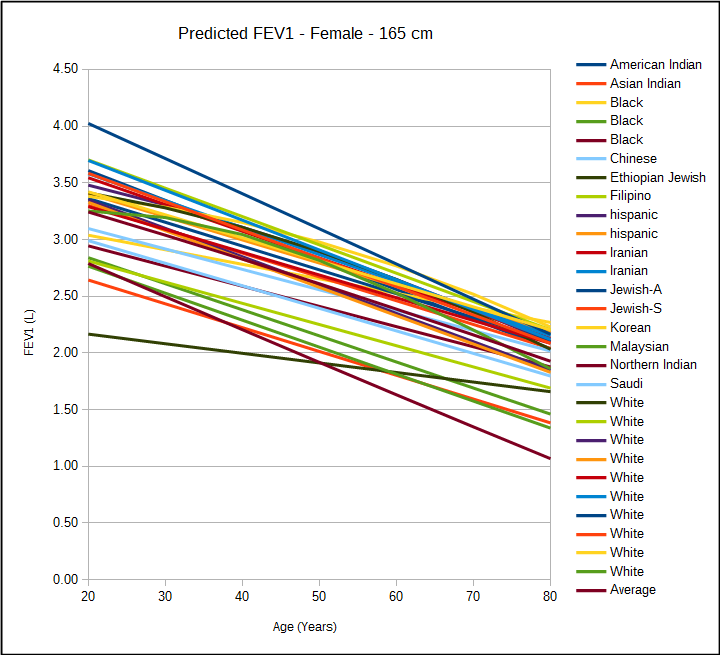

Normal values are based on an individual’s age, height and gender. When this information is entered incorrectly the normal reference values will also be incorrect. These errors often go uncaught because whoever reviews and interprets reports usually isn’t the same person who sees the patient and performs the tests. This type of error often doesn’t get corrected until the results are uploaded into a hospital information system or the patient returns for a second (or third or fourth) visit.

1. Wrong gender.

Pulmonary function reference equations are gender specific and for individuals with the same age and height, men will have a larger FVC and FEV1 than women do. When a patient’s demographics information is manually entered into a PFT system it’s always possible for somebody to enter the wrong gender. When this happens the predicted values will be either over- or under-estimated. This happens in my lab at least a half a dozen times a year and it’s why when I review reports I try to check the patient’s gender right after reading their name.

This is also a problem area for individuals who have gone through gender reassignment (transsexuals). An individual’s physiologic/developmental gender needs to be used to generate predicted values but this may be at odds with their gender recorded in a hospital’s information system. Some PFT lab systems populate their demographics information from their hospital’s information system when an order is received and it may or may not be possible to alter gender once this has happened. In other cases, an individual’s demographics may be cross-referenced when PFT results are uploaded into hospital information system and may throw an error if the wrong gender is present.

2. Wrong height

All lung volumes and capacities scale with height. Like any other manual entry height can be mis-entered and the most common error I’ve seen is for somebody to enter 60 inches when they meant 6 feet 0 inches.

Height can also be mis-measured if the patient isn’t asked to remove their shoes or to stand straight, or if the patient is asked for their height and it isn’t even measured. An error of an inch or two probably won’t make a big difference in a patient’s predicted values (particularly given the discrepancies between different reference equations) but for somebody who’s on the edge of normal and abnormal it can make a significant difference in how a report is interpreted.

Continue reading →