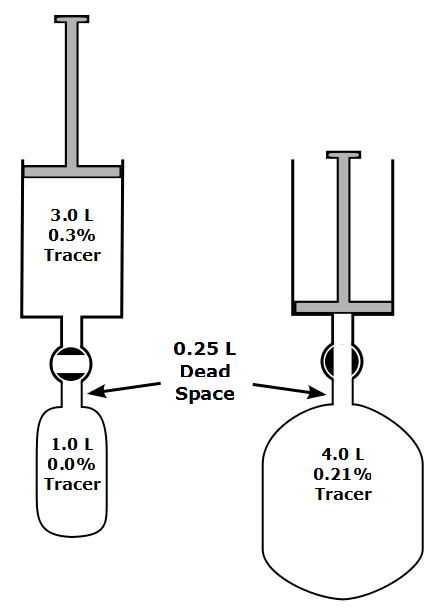

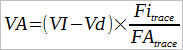

One of the recommendations in the 2017 ERS/ATS DLCO standards was that VA should be calculated using a mass balance equation. I’ve discussed this approach previously, but basically the volume of the exhaled tracer gas is accumulated over the entire exhalation and the amount of tracer gas presumed to remain in the lung is used to calculate VA. The conceptual problem with this for DLCO measurements is that VA is calculated using the entire exhalation but CO uptake is based solely on the CO concentration in the alveolar sample. Since VA calculated using mass balance tends to be larger than VA calculated traditionally in subjects with ventilation inhomogeneities this mean that DLCO calculated with a mass balance VA is also going to be proportionally larger as well.

This problem has concerned me for a while but what wasn’t clear was what difference should be expected in the VA (and DLCO) when it is calculated both ways. In order to figure this out I’ve taken a real-world example of a subject with severe COPD and calculated the difference in VA and DLCO.

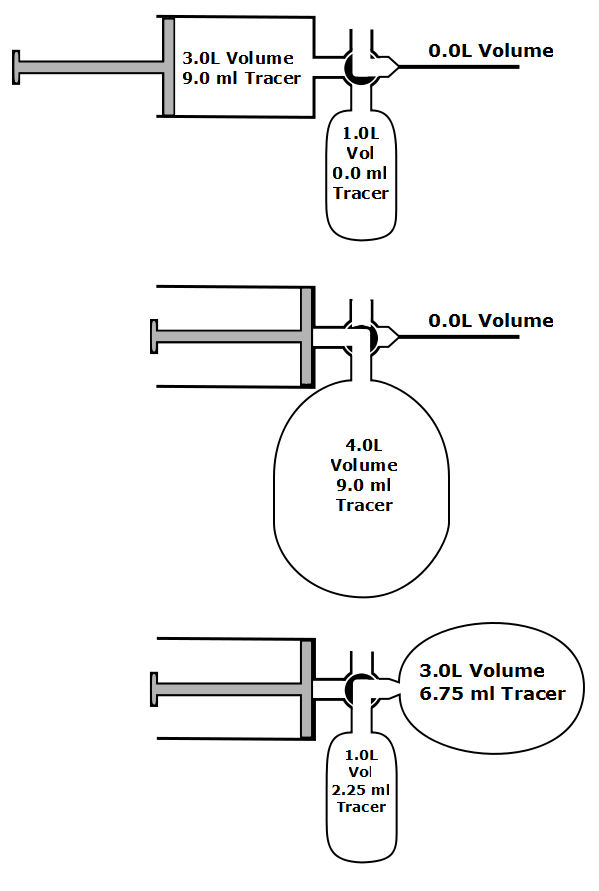

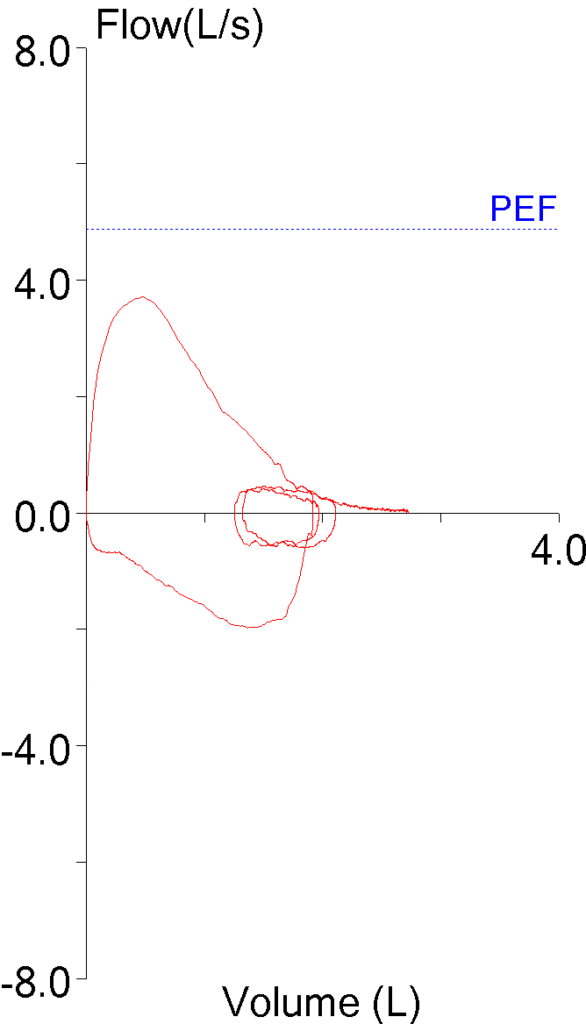

Fortunately, my lab software lets me download the raw data for DLCO tests (volume, CH4, CO at 10 msec intervals) into a spreadsheet. The PFT results for the subject looked like this:

| Observed: | %Predicted: | |

| FVC (L): | 2.39 | 97% |

| FEV1 (L): | 0.66 | 36% |

| FEV1/FVC: | 27 | 38% |

| TLC (L): | 6.11 | 126% |

| FRC (L): | 4.84 | 174% |

| RV (L): | 4.04 | 171% |

| DLCO: | 9.21 | 57% |

| VA (L): | 3.19 | 68% |

| Vinsp (L): | 2.32 |

In order to use the mass balance approach with the spreadsheet I found that I could determine the start of exhalation after the breath-holding period but determining where the alveolar plateau started was much more difficult. For this reason I had to include the dead space but made adjustments for this when calculating VA.

To start off with, using the inspired volume and concentration of CH4 in the DLCO test gas mixture, the volume of inhaled CH4 was:

2.32 L x 0.003 = 6.96 ml.