This is the time of the year when it’s traditional to review the past. That’s what “Auld lang syne”, the song most associated with New Year’s celebrations, is all about. I too have been thinking about the past but it’s not been about absent friends, it’s been about trend reports and assessing trends.

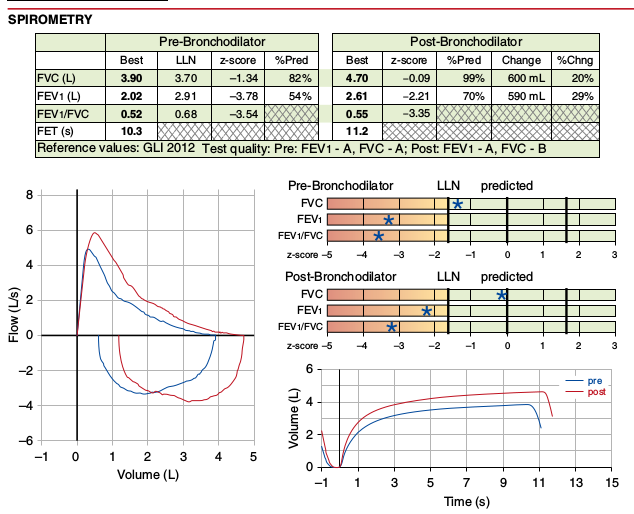

In the May 2017 issue of Chest, Quanjer et al reported their study on the post-bronchodilator response in FEV1. I’ve discussed this previously and they noted that the current ATS/ERS standard for a significant post-bronchodilator change of ≥12% and ≥200 ml penalized the short and the elderly. Their finding was that a significant change was better assessed by the absolute change in percent predicted (i.e. 8%) rather than a relative change.

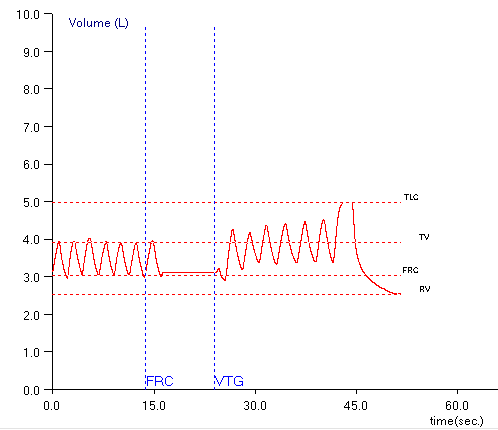

I’ve thought about how this could apply to assessing changes in trends ever since then. The current standards for a significant change in FEV1 over time (also discussed previously) is anything greater than:

which is good in that it is a way to reference changes over any arbitrary time period but it also looks at it as a relative change (i.e. ±15%). A 15% change however, comes from occupational spirometry, not clinical spirometry, and the presumption, to me at least, is that it’s geared towards individuals who have more-or-less normal spirometry to begin with.

A ±15% change may make sense if your FEV1 is already near 100% of predicted but there are some problems with this for individuals who aren’t. For example, a 75 year-old 175 cm Caucasian male would have a predicted FEV1 of 2.93 L from the NHANESIII reference equations. If this individual had severe COPD and an FEV1 of 0.50 L (17% of predicted), then a ±15% relative change in FEV1 would ±0.075 L (75 ml). That amount of change is half the acceptable amount of intrasession repeatability (150 ml) in spirometry testing and it’s hard to consider a change this small as anything but chance or noise. It’s also hard to consider this a clinically significant change. Continue reading