From Darling RC, Cournand A, Richards DW. Studies on the intrapulmonary mixture of gases. III. An open circuit method for measuring residual air. J Clin Invest 19; 1940: 609-618.

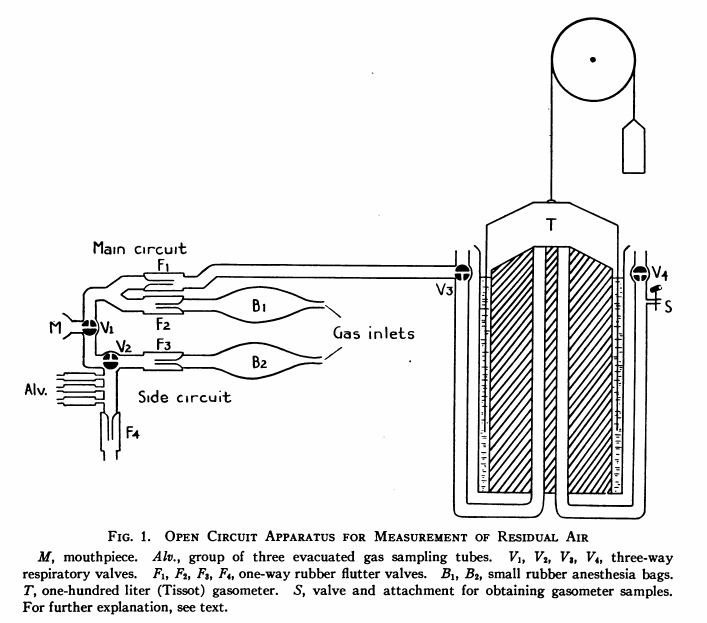

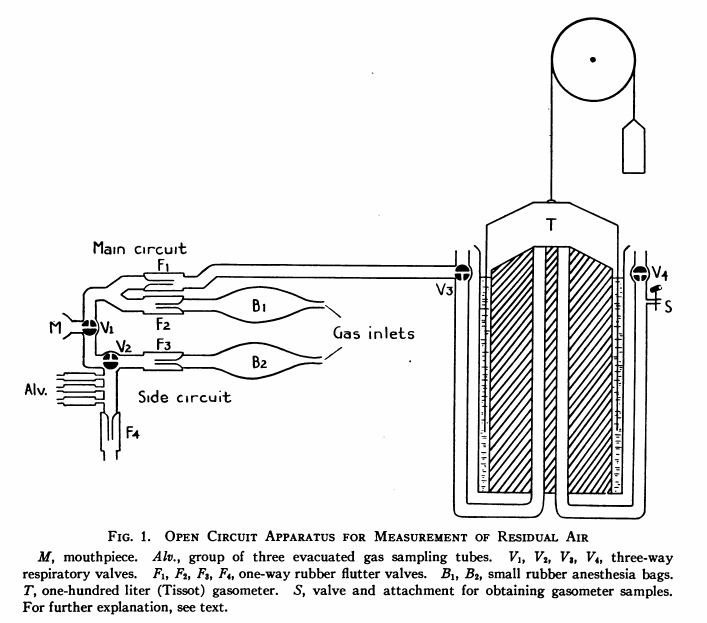

“The arrangement consists essentially of two open breathing circuits fitted with flutter valves (F1, F2, F3, F4) connected adjacent to the mouthpiece (M) at the valve (v1) which cane be used to shift the breathing from one circuit to the other. One circuit, the main circuit, is attached on the inspiratory side to a rubber anesthesia bag (B1), this in turn to an oxygen tank. The expiratory side leads to a Tissot gasometer of 100-liter capacity. On the side circuit there is an additional valve with which the inspiratory gas flow can be cut off during alveolar sampling. The inspiratory arm of this circuit leads to an anesthesia bag (B2) and oxygen tank, which were replaced by by a tube leading from outside air when atmospheric air was the desired breathing mixture. On the expiratory arm evacuated sampling tubes labeled “alv” are inserted close to the valve (V2). The dead space from mouthpiece to these tubes is about 100 cc.

“The procedure for determination of functional residual capacity air by the open circuit method was started with V1 turned to the side circuit. The main circuit and gasometer were thoroughly washed out with oxygen. Six successive washouts of 10 to 20 liters each were found adequate. After the washing, V2 was opened to connect the main circuit to the open room and a flow of 4 to 5 liter per minute of oxygen was maintained in this circuit. The bag (B2) in the side circuit was replaced by a room inlet tube. Then with V1 unchanged, the subject under basal conditions, was attached to the mouthpiece. When breathing quietly, he was instructed to exhale maximally for an alveolar sample. At the same time, the valve (V2) was turned to close the inspiratory side of the circuit. The alveolar sample was taken at the end of approximately 5 seconds of expiration and V2 was reopened. The sample, designated “alv.d” was thus a Haldane-Priestly alveolar sample representing an attempted measure of average lung gas concentration on room air breathing.

“Following this sampling, at least two minutes of room air breathing were allowed in order to restore quiet breathing. The V2 was turned to direct the oxygen flow of the main circuit into the gasometer and V1 was turned to the main circuit at exactly the end of a normal expiration. By watching carefully the respiratory rhythm for the few previous breaths, this latter valve turn could be made accurately at the desired moment.

“For the next seven minute of oxygen breathing the expired gases were collected in the gasometer. During this time, the oxygen flow was maintained to keep the bag (B1) about one-half full. The period of seven minutes was the standard one used….

“At the conclusion of the seven minutes, the valve (V1) was again turned to the side circuit, this time at any point during the expiration, preferably near the beginning. At the same time, the subject was instructed to expire fully for an alveolar sample. For this, as for all alveolar sampling, the valve (V2) had been turned to close the inspiratory arm of the circuit. This alveolar sample, designated “alv.p” was taken at approximately five seconds of expiration as before.

“Following this, the patient was disconnected and the main circuit flushed with 5 to 10 liters of oxygen, wash gas being allowed to mix in the gasometer with the collected expirated gas. The valve (V2) was next turned to close the entire gasometer contents, whose volume and temperature were taken. A sample was taken from the gasometer for analysis within one to two minutes after first flushing out the inlet and outlet pipes of the gasometer proper with the collected gases. This sample will be designated as “Tissot” sample in future references.”