The current ATS/ERS standards for a positive bronchodilator response are an increase in FEV1 or FVC of ≥ 12% and ≥ 200 ml. These standards are largely based on the ability to detect a change that is far enough above the normal variability in FEV1 and FVC to be considered significant. One problem with this is that the amount of variability that is considered to be “normal” is overly influenced by a relatively small number of subjects that have a high degree of variability.

At least one group of investigators has suggested that a way around this is to subject all of an individual’s pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry to statistical analysis in order to determine their coefficient of variability. Once this is known, the pre- and post-bronchodilator efforts can be assessed as a group to determine whether whether there has been a statistically significant change. Using this approach they were able to show that a rather large number of subjects that did not meet the ATS/ERS criteria did have a statistically significant improvement in FEV1.

But an increase that is statistically significant or one that is greater than normal variability is not the same thing as clinical significance. Numerous investigators have noted that patient can have a post-bronchodilator clinical improvement as shown by a decrease in dyspnea or an increase in exercise capacity without any notable change in FEV1 or FVC. Clinical significance is hard to measure however, particularly since which criteria should be used to measure it are unclear.

Long-term survival is certainly clinically significant and a recent article in Chest (Ward et al) has linked the increase in post-bronchodilator FEV1 to this fact. What these investigators have been able to show was that individuals with a post-bronchodilator increase in FEV1 that was 8% of predicted or greater showed a significantly better long-term survival than individuals with a smaller increase.

Strictly speaking this study is not saying that an 8% increase in FEV1 somehow improves survival. What it is actually doing is separating individuals with asthma (which tends to have a reasonably good prognosis) from those with COPD and IPF (which tend to have a poor prognosis). Because this study only looked at an increase in FEV1 it also doesn’t mean that bronchodilators are of no value to patients with COPD (and possibly some with interstitial diseases since combined obstructive and restrictive disorders aren’t all that uncommon).

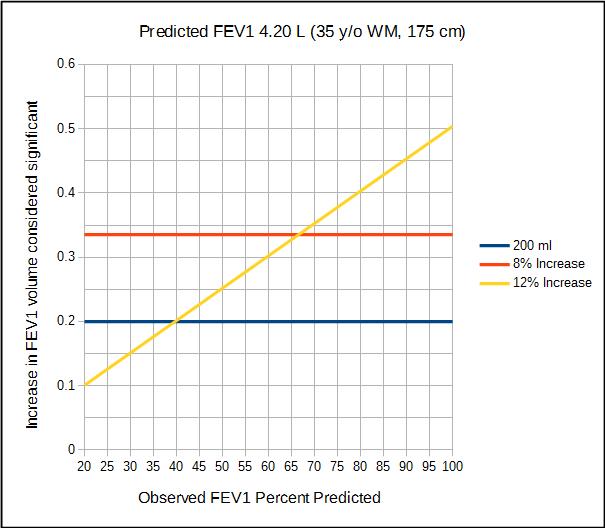

There is a qualitative difference between how a post-bronchodilator increase that is 8% of the predicted FEV1 and one that is 12% of the observed FEV1 are assessed.

When 8% of predicted is used as a threshold for reversibility the post-bronchodilator volume increase that is considered significant is the same for all observed FEV1s. This means that individuals with an observed FEV1 less than 67% of predicted (which because it is actually a ratio 67% applies to all ages and both genders) and a post-bronchodilator volume increase greater than 200 ml, a 12% increase in observed FEV1 will be significant when an 8% increase of predicted is not. On the other hand, individuals with an observed FEV1 greater than 67% of predicted and post-bronchodilator increase of 8% of predicted will be significant when a 12% increase is not. Basically this means than the closer an observed FEV1 is to the predicted FEV1, the smaller the relative post-bronchodilator change in FEV1 needs to be for it to be considered significant. This in turn means that more individuals with mild airway obstruction are likely to be considered reversible while individuals with moderate to severe airway are obstruction are going to be less likely to be considered reversible.

Interestingly, as part of their analysis Ward et al showed that that a post-bronchodilator increase that met the ATS/ERS standard was moderately biased towards males. When an absolute increase in FEV1 (>200 ml) was considered by itself, it was highly biased towards males and this due to the fact that males have larger lung volumes than females. When the increase in FEV1 was expressed as a percent of predicted however, results were neutral to both gender and height.

The bias in the current 12%, 200 ml standard can be seen by comparing this graph with the prior graph. Because of the 200 ml threshold, a 12% increase for a male with an observed FEV1 of 40% of predicted or higher is significant, while a female needs to have an observed FEV1 of 52% of predicted or higher for a 12% increase to be considered significant.

Should a post-bronchodilator increase of 8% in percent predicted replace the current ATS/ERS standard of 12% and 200 ml? I think the answer is a qualified yes primarily because it appears to overcome gender bias and additionally because it also makes the 200 ml threshold a moot point. This yes has to remain qualified however, because it will also skew the distribution of individuals that are considered reversible based on how mild or severe their airway obstruction is and although are reasons to believe it be more correct than the current ATS/ERS standard the effect it may have on patient care and treatment has not been studied.

Long-term survival is one measure of clinical significance, and this study makes a strong case that a post-bronchodilator increase in FEV1 greater than 8% of predicted is a clear and significant threshold. This study only addressed changes in FEV1 however, and for this reason it does not mean that post-bronchodilator increases in FVC or IC (or possibly other values such as PIF) and other clinical improvements such as a decrease in dyspnea or cough frequency should not be considered significant.

References:

Brusasco V, Crapo R, Viegi G. ATS/ERS Task Force: Standardisation of lung function testing. Interpretive strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 948-968.

Hansen JE, Sun XG, Adame D, Wasserman K. Argument for changing criteria for bronchodilator responsiveness. Respiratory Med 2008; 102: 1777-1783.

Hansen JE, Porszasz J. Counterpoint: Is an increase in FEV1 and/or FVC ≥ 12% of control and ≥ 200 ml the best way to assess positive bronchodilator response? No. Chest 2014; 146(3): 538-541.

Pellegrino R, Brusasco V. Point: Is an increase in FEV1 and/or FVC ≥ 12% of control and ≥ 200 ml the best way to assess positive bronchodilator response? Yes. Chest 2014; 146(3): 536-537.

Ward H, Cooper BG, Miller MR. Improved criterion for assessing lung function reversibility. Chest 2015; 148(4): 877-886.

PFT Blog by Richard Johnston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

I would think that, even if the standard for reversibility isn’t changed to 8%, “borderline cases” of reaching predicted FEV1 should be considered as significant.

In other words, if a patient tests at 77% FEV1 value, and post-bronchodilator shows a 9% increase, effectively putting that patient into normal range, post-bronchodilator, it’s significant in and of itself.

Currently, with any post-bronchodilator value that is under 12%, the fact that the patient rose to normal FEV1 level, is basically ignored in terms of reversibility.

If the change in FEV1 value rises from abnormal to normal due to a bronchodilator inhalation, that seems significant, especially if asthma is ruled out.

Ed –

I agree to some extent, I’d point that you can have a “normal” FEV1 and still have airway obstruction and this is because the FEV1/FVC ratio is largely what is used for this determination not just FEV1.

– Richard