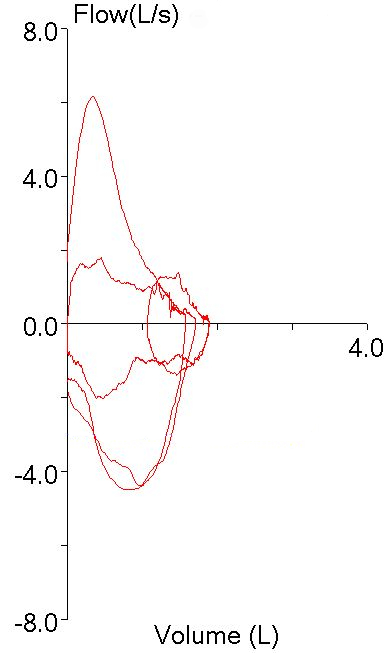

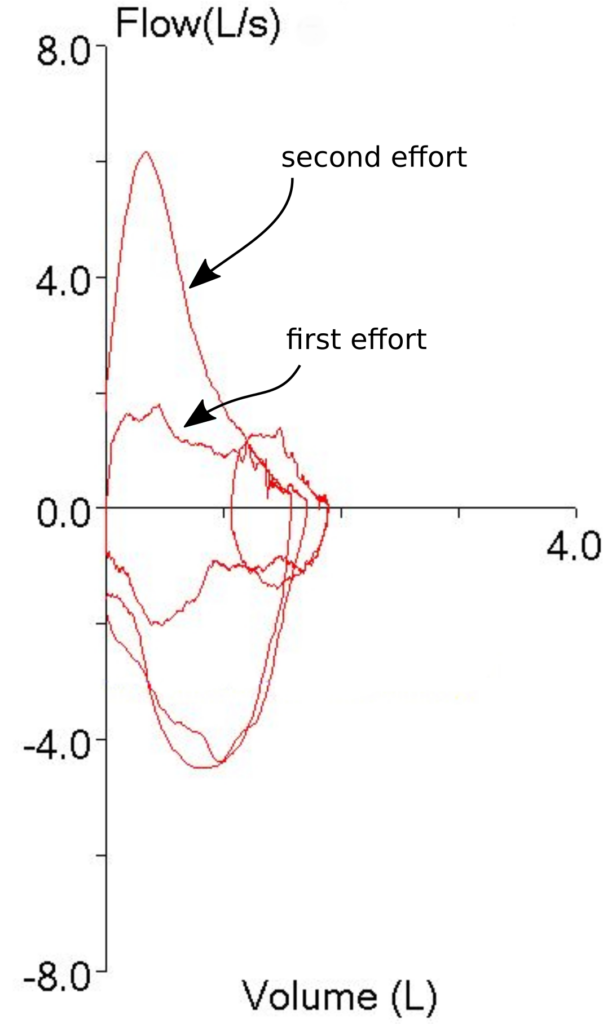

A couple of days ago I was reviewing (triaging, actually) the spirometry portion of a full panel of PFTs performed with pretty terrible test quality and was trying to decide if the technician responsible for performing the tests had made the right selections from the patient’s test results. I noticed that the FEV1 that had been selected was actually the lowest FEV1 from the all the spirometry efforts the patient made, and was trying to decide whether this was really the correct choice. We use peak flow to help determine which FEV1 to select and that particular spirometry effort appeared to have the highest and sharpest peak flow by a large margin:

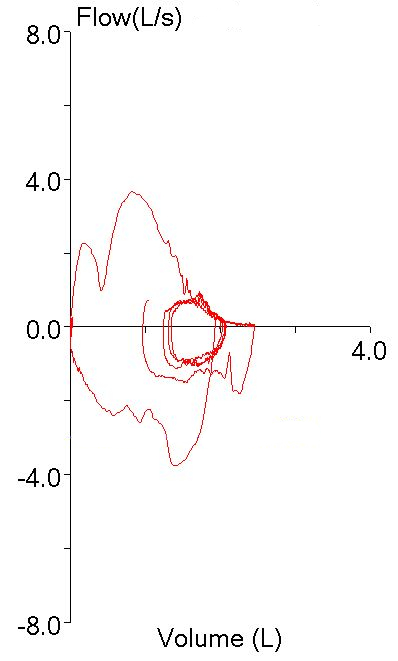

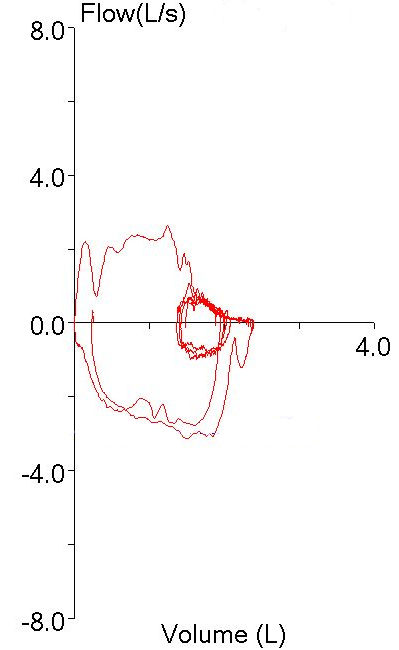

particularly when compared to the other spirometry efforts:

But this was hard to reconcile given how low the FEV1 was relative to the others:

| Test #1 | Test #2 | Test #3 | ||||

| Observed: | %Predicted: | Observed: | %Predicted: | Observed: | %Predicted: | |

| FVC (L): | 1.71 | 41% | 2.46 | 59% | 2.39 | 58% |

| FEV1 (L): | 1.24 | 39% | 1.81 | 57% | 1.77 | 55% |

| FEV1/FVC: | 73 | 95% | 74 | 96% | 74 | 97% |

All of the other efforts though, had significant quality issues that might cause the FEV1 to be overestimated. Effort #2 had a large amount of back-extrapolation (0.32 L, 13% of FVC). Effort #3 also had a lot of back-extrapolation (0.28 L, 12% of FVC) and it also had a blunted peak flow that was substantially lower than the other efforts. Or did it?

I was looking across all the numerical peak flow results and suddenly noticed that the first effort, the one that appeared to have the highest peak flow, actually had the very lowest.

| Test #1 | Test #2 | Test #3 | ||||

| Observed: | %Predicted: | Observed: | %Predicted: | Observed: | %Predicted: | |

| PEF (L/sec): | 1.79 | 21% | 3.66 | 0.44 | 2.64 | 0.32 |

So what was going on here?

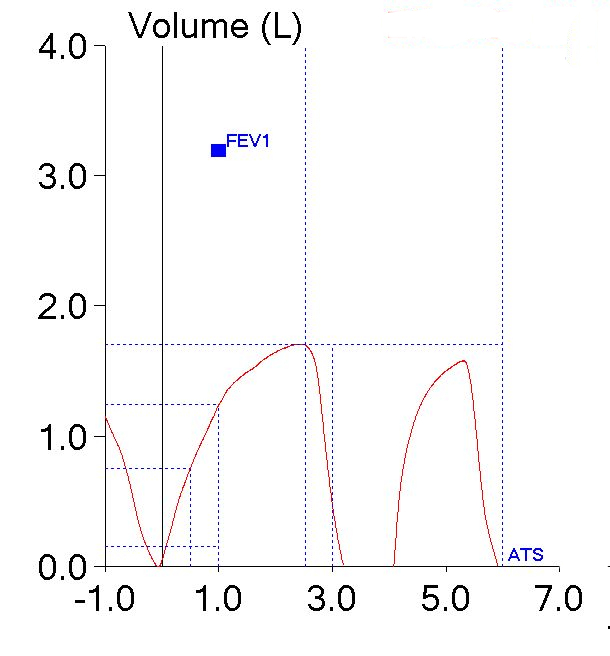

As I said, the patient’s test quality was pretty poor and when I looked at the volume-time curve I saw what the problem was.

The patient had actually made two back-to-back efforts. The numerical values (FVC, FEV1 and PEF) were reported from the first effort. The second effort however, was what produced the flow-volume loop with the highest peak flow. The smaller loop that was inside the maximal loop (which I had taken to be one of the tidal loops and ignored) was actually the first effort.

So, both the technician and I had been fooled by looking at the first effort’s flow-volume loop and taking it at face value. It was obvious that the first spirometry effort had the highest peak flow so the FEV1 from that effort had to be the best and most accurate one, didn’t it? Well actually, no, it didn’t, particularly since we weren’t looking at the right flow-volume loop.

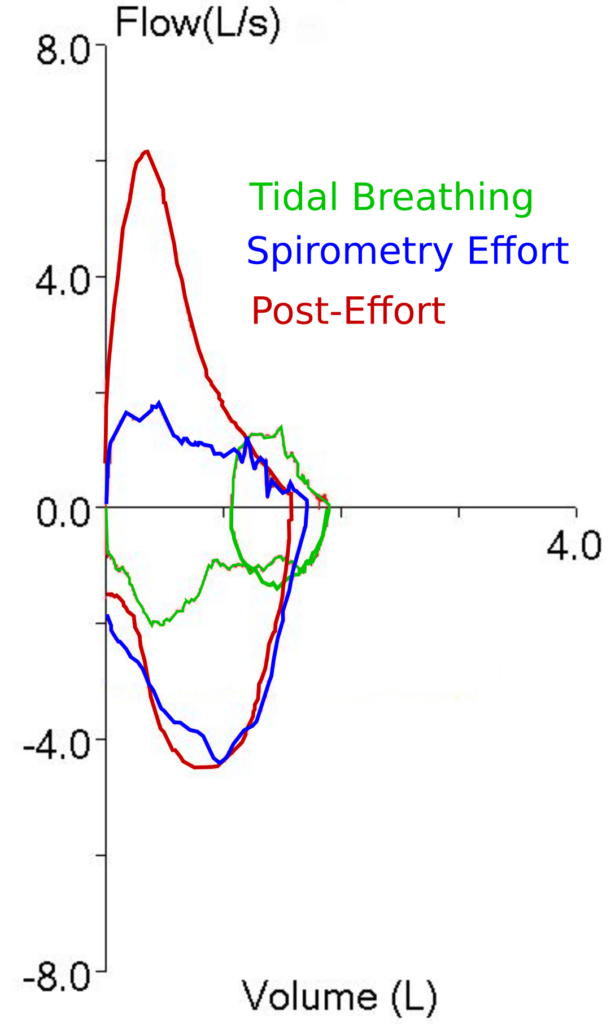

To some extent I blame our lab’s software for this problem. The traces that make up the flow-volume loop are presented in one color with no differentiation between the pre-test tidal loops, the test effort itself, and whatever comes after the test effort. Oftentimes towards the end of an exhalation, the tracings from the tidal loops and the actual spirometry effort frequently overlap and there have been many times when I have wished that the tidal loops were in a different color in order to make it clear which tracing was which (particularly when I’m trying to determine whether the spirometry effort ended at a volume lower than where it started). This particular problem makes it clear that the tracing color should also be different once the end of a spirometry effort has occurred. Maybe if it looked something like this:

then it would be clear which part of the flow-volume loop was which.

I ended up selecting effort #2 to be reported, partly because it had the largest FVC (and longest expiratory time), partly because it had the best PEF and partly because even if the FEV1 was overestimated because of of back-extrapolation, it was still more believable than the FEV1’s from all the other efforts. I also think this was a better choice since if the FEV1 from the first effort had been reported it would have looked like the patient had airway obstruction on top of his restriction (the TLC was moderately reduced) and I just don’t think that was correct.

The fact that I was trying to salvage something out of this patient’s tests results re-raises the question of when results should be reported and when they shouldn’t. You could say that if none of the tests meet the ATS/ERS standards then none of them should be reported and that argument could be made for this patient’s spirometry efforts since none of the spirometry efforts met all of the ATS/ERS standards. The problem with taking this approach is that the ATS/ERS spirometry standards have loopholes. In particular you can take the FEV1 from one effort and the FVC from another. If this was done then the FEV1 from the first effort would have been reported since it was the only one that had essentially no back-extrapolation (0.05 L) and the ATS/ERS standards do not use PEF in any way when selecting FEV1. The effort the FVC would have been taken from was longer than 6 seconds and also met the end-of-test criteria. For these reasons it could be said that the results derived in this way would have met the ATS/ERS standard even though it’s also apparent that the test quality wasn’t particularly good and that the results probably wouldn’t reflect the patient’s status.

There’s also the point that even when test results don’t meet all of the ATS/ERS criteria, they can still answer some questions. For example if a spirometry effort was only 1-1/2 seconds long but the FEV1 was normal, then that makes it reasonably unlikely that there is any airway obstruction even if the FVC is significantly underestimated. I’d say that’s a reason to still report the results. Ditto if the FVC was above the LLN but the FEV1 was mis-estimated due to an expiratory pause or back-extrapolation.

For this patient test quality and reproducibility was poor, but there were still bits and pieces that were able to present a somewhat coherent picture and for this reason (after some editing) I put the report in my out basket.

PFT Blog by Richard Johnston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

The hiccups in the beginning of the expiratory efforts in many people’s opinion makes the entire test unreliable. Why could the test not be repeated such that this was not present?

-Pulmonary fellow, Montefiore, Bronx

Love the site btw keep up the good work.

Dr. Abbasi –

Part of the problem with this and many other spirometry efforts is that the way the computer presents the results often makes it hard to determine there’s an error in the first place. The other part however, is that many patients cannot perform good quality spirometry no matter how many times you try. There’s also the point that like it or not we have limited amount of time we can spend with any patient and that once that time is up, we have to report what we have.

Do you mind if I ask how often you perform spirometry? I bring this up because when I started working in a PFT Lab in the early 1970’s it was expected that Pulmonary Fellows spent a couple weeks in the lab doing routine testing and calculating results from the kymograph paper. That stopped well before the 1980’s because fellows were too busy in the ICU and didn’t have the time to do it any more. Nowadays the closest that most pulmonary fellows (not all) get to the PFT lab is to review reports with an attending physician. Not necessarily a bad thing but it also means that many present-day Pulmonary physicians have no hands-on experience with pulmonary function testing. Technicians are criticized for failing to get good quality results but these criticisms are often made without any understanding of how difficult it can be to get any results, let alone good ones, from some patients.

I’m not going to say that technicians aren’t also part of the problem. Good pulmonary function testing takes a blend of technical, clinical and people skills but all too often it is performed by rote. To some extent I blame the lack of any formal education process for PF techs but to be honest, too many people only want to learn (and do) the minimum necessary to get by. This isn’t helped by the common (mis-) perception, both by techs and medical directors, that the computer is always right.

Sorry to go on but you inadvertently touched on a topic that’s important to me. I’ll get off my soapbox now.

Regards, Richard

Absolutely right a lot of fellows myself included aren’t exposed to that side of PFT derivation unfortunately. Some programs like I know NYU for example does a good job of this actually.

More questions on this case- I don’t see how a 1.5 second effort allows you to rule out obstruction even with a normal FEV1. We see normal predicted FEV1s with abnormally low FEV1/FVC ratios which means there is obstruction. But if effort is so short how can you know the patient is breathing out enough of the air in his lungs for you to confidently say there is no obstruction?

thank you. I’m learning a great deal from your site.

Dr. Abbasi –

You’ll notice I said that airway obstruction was “reasonably unlikely” not that it was completely ruled out. When interpreting test results you always need to think in terms of probabilities, not absolutes. For example, what if the patient’s spirometry effort met all ATS/ERS criteria for expiratory time and EOT flow rates and the FVC, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio were above the LLN. I’m sure we’d all say that the spirometry was normal and ruled out airway obstruction (or something like that anyway). When you look at the trends however, you see that the FEV1 is unchanged but that the FEV1/FVC ratio from the previous visit was below the LLN and this was because the previous FVC was 15% higher and that in turn was because the patient had blown out 10 seconds longer. Now that you know that, despite the fact that the current spirometry is normal”, wouldn’t you say that the probability that the patient still has airway obstruction is fairly high?

The ATS/ERS guidelines are a useful starting point but they have limitations and flaws. I can think of many examples where a test result meets all ATS/ERS criteria yet does not represent “truth”. One very real limitation of learning PFTs only through interpreting reports is that each test is actually performed multiple times and what’s on the report is a composite and the result of test selection by the technician and (heaven help us) the computer software. This selection process goes unseen (and usually un-noticed) but without a “hands-on” understanding of testing idiosyncrasies the interpreting physician is dependent on somebody (or something) else’s judgement for what’s on the report.

Regards, Richard

Thanks Richard.

My question was in regards to your last comments where I believe you were making a general statement–that even if you had a 1.5 second effort for FVC you can still rule out obstruction with good deal of certainty if the FEV1 was normal.

I can see how this may be true for many patients but you will also miss a lot of pts who may have true obstructive disease–as you yourself state you can increase specificity by using the slow vital capacity even if after a BD challenge. Wondering if you have any studies or numbers which may suggest that using just the FEV1 despite inadequate FVC effort can help rule out obstruction.

Thanks again.

Dr. Abbasi –

I’ve not seen any studies that looked at whether just the FEV1 was sufficient to rule out airway obstruction. I’d also agree with you that there will be people with a normal FEV1 who can still have airway obstruction. But when all you have is an FEV1 to work with, a normal FEV1 at least rules out any significant airway obstruction.

Regards, Richard