A while back I reviewed the spirometry grading system that was included in the 2017 ATS reporting standards. My feeling was, and continues to be, that its usefulness is very limited because it’s mostly a reproducibility grading system that relies on a few easy-to-measure parameters. This doesn’t mean that a grading system can’t be helpful, just that it needs to be focused differently.

In a clinical PFT lab many patients have difficulty performing adequate and reproducible spirometry, but that doesn’t mean the results aren’t clinically useful. Moreover, suboptimal quality results may be the very best the patient is ever able to produce. So what’s more important in a grading system than reproducibility is the ability to assess the clinical utility of a reported spirometry effort.

The two most important results that come from spirometry are the FEV1 and the FVC, and I strongly believe that they need to be assessed separately. For each of these values there are two aspects that need to be determined. First, is there a reliable probability that the reported value is correct? Second, are any errors causing the reported value to be underestimated or overestimated? The two are inter-related since a value with excellent reliability is not going to have any significant errors, but if there are errors then a reviewer needs to know which direction the result is being biased.

The current ATS/ERS standards contain specific thresholds for certain spirometry values such as expiratory time and back-extrapolation. Although these are certainly indications of test quality they are almost always used in a binary [pass | fail] manner. In order to assess clinical usefulness however, you instead need to grade these on a scale. For example an expiratory time of 5.9 seconds for spirometry from a 60 year-old individual would mean that there is a small probability that the FVC is underestimated, but with an expiratory time of 1.9 seconds the FVC would have a very high probability of being underestimated and this needs to be recognized in order to assess clinical utility.

Note: Although the A-B-C-D-F grading system is rather prosaic it is still universally understandable, so I will use it for grading reliability. An A grade or an F grade are probably easy to assign but differentiating between B-C-D may be more subjective, particularly since reliability depends on multiple parameters and judging their relative contribution is always going to be subjective at some point. For bias, I will be using directional characters (↑↓) to show the direction of the bias (i.e. positive or negative), so ↑ will indicate probable overestimation, ↓ will indicate probable underestimation, and ~ indicates a neutral bias.

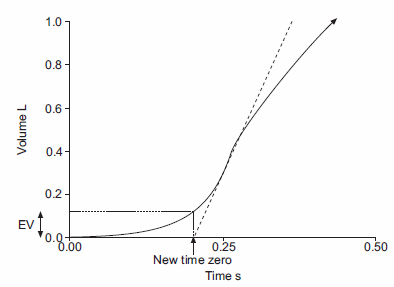

FEV1 / Back extrapolation:

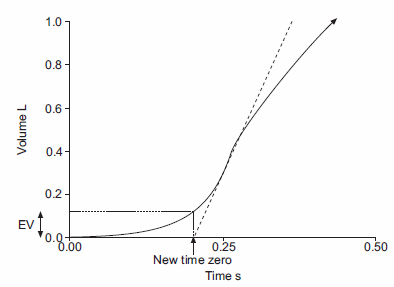

Back-extrapolation is a way to assess the quality of the start of a spirometry effort and the accuracy of the timing of the FEV1. The ATS/ERS statement says that the back-extrapolated volume must be less that 5% of the FVC or less than 0.150 L, whichever is greater.

My experience is that an elevated back-extrapolation tends to cause FEV1 to be overestimated far more often than underestimated. So a suggested grading system for back-extrapolation would be (and I’ll be the first to admit these are off the top of my head and open for discussion):

| FEV1: |

|

|

| Back-Extrapolation: |

Reliability: |

Bias: |

| Within standards: |

A |

~ |

| > 1 x standard, < 1.5 x standard: |

B |

↑ |

| > 1.5 x standard, < 2 x standard |

C |

↑↑ |

| > 2 x standard, < 2.5 x standard: |

D |

↑↑↑ |

| > 2.5 x standard |

F |

↑↑↑↑ |

Continue reading →